AA CASTLE IN UMBRIA ★★By Adrian Perez

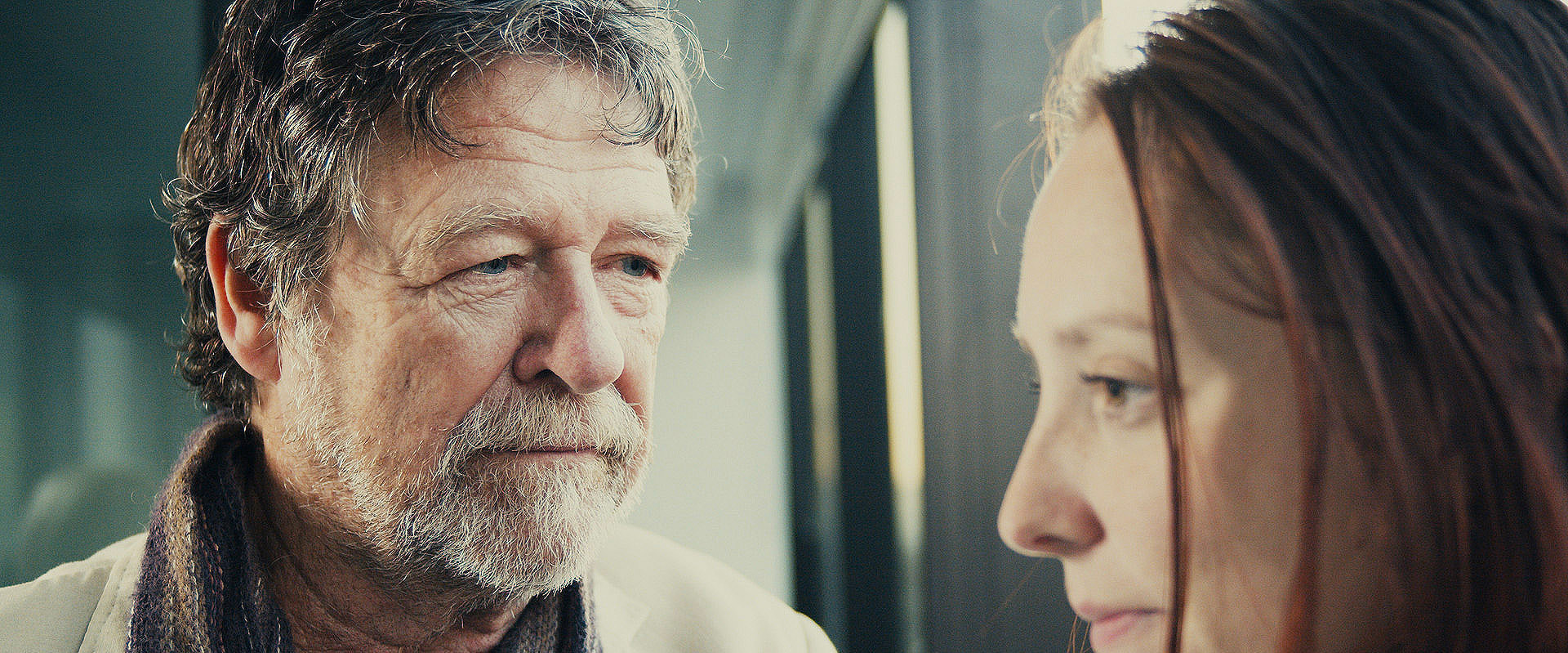

Terry Ross takes her directorial debut to the Italian dreamscape that is Perugia, exhibiting giant ambition in commanding an ensemble cast through its multi-strand dramedy. A Castle in Cumbria entreats us to breathtaking aerials and intricate scenography, though the film’s narrative and performative facets demand the same calibre. What looks to have been a fun production doesn’t convey as potently onscreen due to Ross opting for a corporate drama, which in effect results in underplayed performances for the narrative requires quite grounded dry performances devoid of any hyper-drama or comedy (which is where the entertainment value’s at). The moment when Rick and Charlotte meet after forty years (which is a mighty long time) feels immensely underplayed, I can’t help but feel it was a missed opportunity for a carefully-calibrated mix of tension and comedy to make for a memorable scene. On an editorial level, Ross injects a musical score into most scenes to compensate quite flat scenes, devoid of any real tension, drama or comedy. Whilst A Castle In Cumbria invokes a fondness from me for its impressive locales and production value, it just needs to up the stakes or the comedy, it gets stuck in a cyclical mundanity. Nevertheless, the sheer scale of the project equate Ross’s ambition and passion for the craft, I long to witness Ross’s evolution. A HOME FOR CURIOSITIES ★★½By Adrian Perez

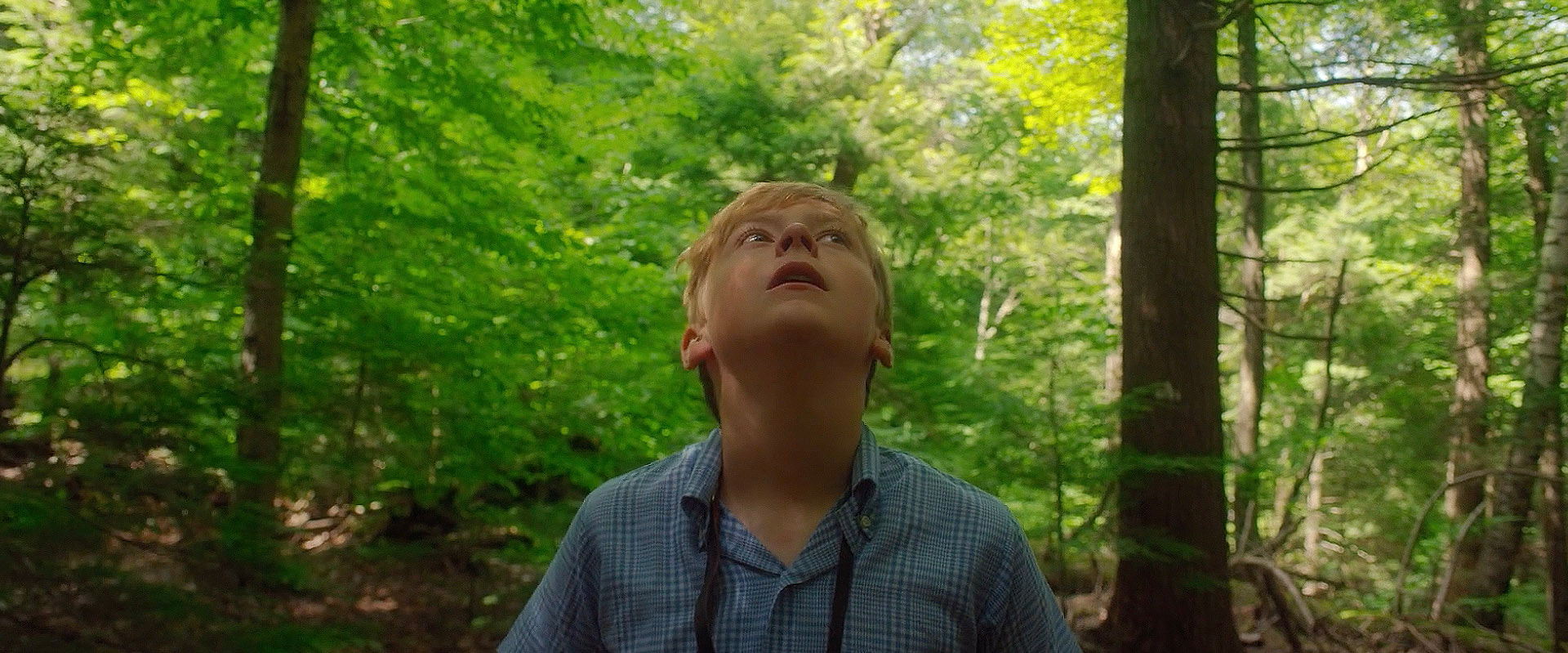

Tobin’s A Home For Curiosities evokes great endearment; as we dive deep into the forest where quirky young Wallace passes the time birding (“birdwatching in layman” as Wallace points out)—we in fact are also entering his dream realm. His imagination leads us to a strange big mansion inhabited by forgotten imaginary friends (“Curiosities” as Wallace calls them); enthralled by their wonder but concerned by their fateful demise he decides to pair them up with real kids to make some pocket money. Tobin’s directorial vision and stylistic stamp are prominent throughout, there’s a very fine balance between physical and tempo-rhythmic comedy, and the ethereal audiovisual manoeuvres Tobin employs to capture Wallace’s perception of Adelaide and the other Curiosities. These contrasting traits in Tobin’s quirky whilst ethereal odyssey provide a refreshing fusion of ingredients from antecedents such as Bridge to Terabithia and Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. Where Tobin’s vision halts from transcending is in jam packing quite a special high-concept in limited screen time. Tobin deposits such a colourful fresh concept onto us and in working within the small canvas that is a short film of 15 minutes it can feel brushed off and resolved too abruptly. On an editorial, performative and cinematographic level—the story’s high-concept demands more intricacy and refinement; where Tobin undeniably soars is in his unique approach to visual storytelling, unafraid to experiment and crossover genres. A Home For Curiosities pitches a refreshing high-concept and serves a trailer for Tobin’s talents and level of ambition, that I long to see fully-realised and refined in a bigger-scale canvas where his imagination can run free much like his lead protagonist’s. AGATHA ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Much like Jørgen Leth’s The Perfect Human offers an examination into human behaviour in a suave pseudo-scientific way, Julián De La Chica flicks the switch to observe a homosexual man in his natural habitat through a similar ethereal black and white presentation. The results are contrived much like Leth’s experimental canvas. De La Chica makes Próspero (Guzmán) grotesque from the get-go, through close-ups of his scrotum, to him fingering his ass crack to then swirl his drink with the same fingers. Próspero is also hyper-feminised, from a predominantly cross-legged posture, to flamboyant mannerisms and cross-dressing inclinations. De La Chica further makes Próspero unkempt. All directorial calibrations that defy aspirational masculinity and attractiveness in a gay culture that favours perfection, ribcage muscles and smooth hairless skin. There is something Almodovarian about De La Chica’s work; though Almodovar’s lens idolises male body perfection, De La Chica’s romanticises imperfection to the point of repellence. De La Chica exhibits directorial competency in creating a fully-realised canvas; through his melancholic score, long takes and unkempt man and cave surrounded by alcohol and drugs, Agatha evokes isolation and loneliness, unfulfilled sexual desire and repression, and depression to the point of self-termination. Agatha serves a provocative, whilst imperfect (much like Próspero) examination into the inherent interconnection between homosexuality, transsexuality and solitude, depression and suicide—by merely placing us to be the observer. De La Chica makes his own cameo as Carlos, narrator of the story who observes Próspero/Agatha from across the street, and in his mere watching depicts society’s lack of intervention (which might as well equate to oppression in the form of marginalisation). Powerful experimental film that strives to be unpolished, for we are all imperfect. AUDITION ROOM 2 ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Audition Room 2 is quirky, unpredictable, radical; not what you would expect at all of a directorial debut which makes it all the more commendable. Newell proves a tenacious visual storyteller who gets away from muffled sound design and the typical cues that help interpret interiority, to depositing metaphorical cues and ambiguity instead in her social vignette of an audition room. Through portable mascot cages to bizarre acts of self-infliction, Newell depicts these actresses’ differing personalities and states of being as they await to go into their audition. Audition Room 2’s surrealistic vignette— through these actresses’ radical acts of self-sabotage and destruction as well as their attempts at eradicating their competition in each other—amplifies the angst of such a trialling scenario. Newell delivers a highly experimental and all the more memorable film. A stellar debut. AVATAR GATES OF POWER ★★★By Adrian Perez

Salmon and Regalmuto invoke a detachment from our physical vessels to transcend beyond on this spiritual odyssey; through a soothing soundscape and breathtaking nature aerials Avatar Gates of Power brings us closer to ourselves in our self-acceptance, through to our self-healing and then self-love. This dynamic duo in Salmon and Regalmuto deliver a poetic visual spectacle that leaves little for the critical eye to contest; where this presentation could find elevation is in a more minimalistic setting and backdrop, for the interiors can prove crowded for spectators who in their pursuit for spiritual connection also seek transcendence from minimalism. A formidable directorial debut for these two auditory champions. BBEHIND THE NAME 'SHAKESPEARE': POWER, LUST, SCORN & SCANDAL ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Art is said to depict life itself, and Robin Phillips’s documentary—four years in the making—comes to the same culmination, for “Shakespeare” often penned protagonists who found themselves humiliated in their disownment/dethronement from status or royal privilege, and he could be said to have suffered the same fate as his fictional characters. Phillips has amounted a formidable resume having lived in twelve important cities of the world, whilst an alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and the Editor in Chief at Washington Entertainment, amongst infinite career ventures that make her a rare multilingual multidisciplinary artist. Behind the Name ‘Shakespeare’ was the offspring of an authorship predicament that was imposed on her, that “Shakespeare” wasn’t in fact the credible timeless literary master behind his oeuvre, but the 17th Earl of Oxford: Edward De Veer. Years of silent study and research bring Phillips to her provocative performative documentary, that comprises most intricate arguments and valid commentary for irrevocable findings. For a predominantly self-made documentary, Phillips deserves enormous credit and recognition; the documentary’s only downfall is perhaps its technical quality—though competent and impressive in the context of its making, it does beg an even more polished execution (better camera, sound and editing all-in-all). Insightful and with a playful presentation, this is a memorable documentary that I would easily see incorporated into the English national curriculum. BROKEN GAIETE ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Abdelmoula delivers a distressing semi-biblical film in Broken Gaiete, through its dystopia Abdelmoula disentangles and radicalises societal struggles with religion, communism and dictatorship that have led to innocent blood being shed throughout humanity’s history. Mad Max meets Midsommar in these foreigners (in Idier and Kashou) destabilising a cult in a slick gold tint presentation. Suffering with short-term memory loss, Idir and Kashou (a woman who claims to be his mother) stumble on a village and soon get accustomed to their ways. When Idir falls in love and marries Beda, a chain of ritualistic mandates ensue that force him into performing his first sexual act with his wife in front of the elders, and condemn his mother to death at the expense of the birth of his newborn child. All grotesque and macabre acts imposed by a rulebook no-one has ever read (the “golden book”). Abdelmoula has art imitate life, for Broken Gaiete’s narrative pokes at how the bible has been accountable for the persecution and capital punishment of homosexuality for the most part of humanity’s history, and is still prevalent and punishable in sharia-based countries to this very day. Dictatorship and communistic ideologies are also explores within this little tribe. Abdelmoula’s cautionary tale summon the mistakes of our past to defy our present. Broken Gaiete boasts most intricate scenography and costume design, the same can’t be said for its cinematographic calibre and suave screenplay. Abdelmoula’s dystopian epic could use better dialogue construction and a more fast-paced rollercoaster script. It’s two thirds of the way through that Idir finds out of his “mother’s” condemned fate and the village’s underlying macabre agendas, and that really feels the driving force of the story. On a cinematographic and editorial level, the film begs for more artistry and experimentalism to depict Idir’s interiority of disorientation (from his memory loss) and hysteria (from the cult’s ways), for a more immersive and entertaining spectorial experience. What is clear is that Broken Gaiete exhibits an astronomical level of world-building through its scenography for which it must be commended, a formidable production achievement. Abdelmoula proves in his directorial debut his ambition and passion for the craft, and most importantly employs the craft for philosophical effect. Abdelmoula is one to watch. BROXOTIC AND THE TIGER KINGS - GO RONA RONA ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Calvin and Crable are proving a dynamic duo for everything they touch turns into comedic gold. It’s no surprise to see Broxotic & The Tiger Kings’ ‘Go Rona Rona’ spoof music video go viral for it’s flawlessly-executed and evoking of infectious laughter. From the genius lyrical work that pokes fun at our Coronavirus crisis, to Crable’s sensuous guitar work and unapologetic performance, this is a home-run of a parody music video. Bravo boys. BUNKERS ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Bunkers, or shall we say ‘bonkers’ for what a fantastical rollercoaster ride Ollie Anderson entreats us to in his directorial debut. Nothing screams passion more than Anderson’s hand-crafted animation here, from his intricate golf bunker set designs to his barbie and action figure protagonists in Starlo Von Sourdough & Co. he fabricates his very own Wonderland. Will you dare go down the rabbit hole to discover the world of Bunkers? A formidable debut in stop-motion animation and one of the best solo projects to come to fruition during 2020’s pandemic. CCHRISTMAS STORY ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Credit Bank of Moscow’s Christmas ad film ‘The Christmas Story’ can be best described as a misconstrued relic; a philosophical visual spectacle that was met with a flood of backlash and oppositional readings for audaciously making Santa and a working mother antagonists. Charley Stadler’s Christmas epic is inherently a cautionary tale in the style of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Much like Ebenezer Scrooge’s grumpy nature and morality needed to be defied, Stadler chooses a female protagonist through which to focus the morale of his story. We’re met with a wealthy business woman who’s worked to the bitter end to her daughter’s detriment who she marginalises; when the little girl’s wishlist makes its way to Santa requesting nothing more than her mommy back, Santa takes action. Stadler has Santa kidnap the mommy to go to what seems like the end of the world and beyond to look for the little girl’s Christmas gift. A mission of a quest that takes them through breathtaking landscapes and even some of nature’s hellscapes to reach their destination. Just like Frodo’s journey to Mordor they come to a halt as Santa’s health worsens, and then it’s her who has to uplift Santa so they complete their mission. Our mother does a 360 in her journey from showing initial resistance to change, to becoming the change, finding herself and her salvation. Sometimes in life we have to inflict a little hate for love, it’s called tough love. Santa has to give the mommy a little push to get on a journey of self-discovery to realise what truly matters to her in this life. As brilliant as this modern-tale is, it came under attack by a feminist lens which read the film to filth claiming it suppresses women’s career fervour over their maternal responsibilities. Nothing’s more problematic than this oppositional reading’s reductionism of a film that majestically depicts a universal morale. Whilst sensitivities towards the film blew up social media like gunpowder, the press never caught sight that the decision for a mother protagonist as opposed to a father, came from female clients. Food for thought. The tale’s execution is flawless, from two-time Grammy winner Adrian Bushby and Von Seefeld’s hair-raising orchestral score, to Ivan Solomatin and Stadler’s cinematographic language, to the ascertained casting choices and powerful performances, to the film’s wondrous scenography. This Christmas tale is transcendental for it reminds us in an age where materialism overrides connection, to nurture our connections and hold onto our loved ones. Chapó Charley Stadler & Co. CHUCK WONDERLAND - FREE LIKE A BIRD ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Much like Wonderland’s penned lyrics, this striking runaway couple declare themselves free with a bag full of money and drive to the isolating vastness of a valley to experience intimacy and passion, but torment, and ultimately they meet their fatality. But why? Humbert delivers in this cryptic music video for Chuck Wonderland’s hit ‘Free Like A Bird’a slick and sexy cinematographic presentation; one that will open up an infinitude of questions and place the power on you to rationalise these lovers’ fate, like Wonderland declares in his country anthem, you’re free like a bird. CNUT ★★★½By Hannah Brown

Courtney Westbrook’s CNUT understands the power vested in animation to illuminate deeply resonant moral issues. CNUT projects its doll-sized world onto the watery surface of the viewer’s mind and from there, its themes refract new interpretations after every viewing. Westbrook’s intention to highlight ‘technological barriers and distress’ is equally subjective in its allusions; “technology” can range from the localised obsession with your phone to the broadscale hubris of global warming - the reading of it all lays in your hands. For all of this and more I wanted to love CNUT, and though it reaches to create tension between surface and depth, there is something missing in the balance it ultimately strikes. Westbrook cites the ancient tale of King Cnut of Denmark as inspiration for Barry Staff’s script. The sea in the original story represents Nature and God’s power, towards which King Cnut shows his humility. Harnessing that metaphor but subverting the lesson, CNUT casts in miniature man in a state of technology-induced myopia, entering blindly into unrelenting waves. There are some brilliant small moments that do justice to this narrative, such as showing the results of the third selfie attempt only through the double faces reflected in a phone screen to capture technology in its distorting and all-consuming glory. Other choices, such as the synth string music, push our sense of distortion into something tonally confused, like we are journeying into a quasi-horror space fantasy. From the wind-tossed flowers in their earlier project, Theo and Celeste, to the ceaseless ocean waves in CNUT, ARACOURT Studios infuse their stop-motion projects with vitality by capturing nature in motion. The landscapes they construct walk the line between realism and surrealism, half-way between other-worldly painting and tactile human reality. CNUT exists somewhere in the territory of mirage, with its iridescent cellophane waves and a beach-desert that could just as well be the moon. What ARACOURT got so right in Theo and Celeste was the resonant emotional relationship that anchored the beautiful surrealism of their animation style. In CNUT, a wordless, fantastical stop-motion short, we are left to rely on gesture, sound and symbolism to interpret and emotionally respond to the story. Unfortunately, these key visual details characterise the protagonist as an older, grandfatherly figure and therein misdirect the film’s intended focus. Through voice and costume CNUT inadvertently generates in seconds a whole network of associations that tell us we are watching an, albeit adorable, tale about the older generation’s struggle to keep up with modern technology, which limits rather than embraces the allegorical potential of this short. CNUT excels in the stop-motion medium by using brevity and a lack of dialogue to feel deceptively simple, while navigating mature thematic terrain. Some reconceptualising of character and sound would have ensured the complex ideas woven into CNUT remained joyously enigmatic, only to be unravelled in the aftermath of this stunning odyssey into the deep. CRACKS ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Cakiroglu instills numerous underlying themes within Cracks, it’s most fascinating to see how Cakiroglu orchestrates picture and sound to peel off Dr. Emma Willborn’s (Bryan) facade from a put-together neuropsychiatrist to an impostor for her very own repressed trauma and memory. A twist of fate in an unprecedented encounter with an old-time friend she doesn’t remember destabilises Dr. Willborn; throughout her day’s therapy sessions with various clients we see her become insecure to exhibiting impostor syndrome, we see her go from an avid listener to a mind-dweller. Cakiroglu implants cues throughout to suggest Dr. Willborn is as guilty as her many patients in repressing her past memory and trauma. It’s a haunting portrayal of how a strong facade can come crushing down when destabilised; a metaphor for how as humans we build an exterior as a defence mechanism to protect us from our inner demons, and in worst case scenarios to conceal graver psychiatric disorders that lead to a fragmentation of the self and Dissociative Identity Disorder. For a directorial debut Cakiroglu architects a most mature metaphorical film wrapped in a flawless cinematographic presentation, all that can be contested now on Cakiroglu is to not be afraid to get even closer and deeper to her protagonists to see what harsher truths can be scooped out. A formidable debut to be infinitely proud of, the start of a promising career. CRANBERRY ★★★

By Adrian Perez

Buchanan pens in a constrained time frame a harsh turn of events, that of two friends at first longing for inseparability to then admitting their inadequacies and officializing their rupture. A heartbreaking screenplay that depicts the test a geographical move inflicts on friendships. Many of our friendships throughout our lifetime prove merely convenient but nontranscendent; that’s the heart of Cranberry. The film’s score cuts in exactly where it should, as well as the awkward pauses; Sivert showcases tenacity in her film’s tempo-rhythmic construction. Though Cranberry exhuberates maturity and substance, it requires technical refinement to level it up and make for a truly transcendent film. Sivert exhibits in the minimalistic two-hander vignette that is Cranberry a most mature directorial curiosity for human interaction and the volatility of friendship. dDISPLAY HOME ★★★★

By Adrian Perez

Display Home really is unlike anything you’ve seen before. Walls architects a dystopia that will haunt you. Much like Ed and Lotti’s initial reluctance walking into their potential purchase of a replacement daughter, the same can be said of our spectorial experience. Spielberg’s Artificial Intelligence is one of the rare few cinematic explorations of such phenomena, only that Display Home doesn’t deal with exact A.I. replicas of our loved ones, but human actors who meet a physical resemblance and offer themselves to fill that emotional void on a full-time contract. Underneath Display Home’s ingeniously lighthearted facade lays a sinister societal construct that endorses “consenting” modern-day slaves for emotional replacement and fulfilment. Walls leaves us a few breadcrumbs throughout to peek beyond this glasshouse into a decaying pre-apocalyptic backdrop that sees 39% unemployment and humanity scavenging for survival in the form of “stability”, via getting “purchased” or “abducted” into a family unit to fill an emotional void. That seems the only way to survive the hellscape depicted beyond the glasshouse. When Terina seems to have struck a chord with Ed and Lotti; she seems disinclined to sign her ownership away for something’s off with Ed—and it’s suggested at one point he may well have murdered his missing daughter. Within the short’s runtime we have a punching inciting incident for what could be an exhilarating understated horror spectacle. Walls managed a witty, clever and sinister short film; perfectly balanced and inciting of a feature-length treatment. Walls sits on a high-concept worth placing a big bet on. DORSIA ★★★★★

By Adrian Perez

Fasulo orchestrates picture and sound to arresting effects in his latest cinematic exercise; from his choice of an intimate hand-held one-shot take locked on Davide Rezzoli (Balzarolo), to the accompanying pulsating bass synth track to internalise his nerves at not getting in, Fasulo transports us into Davide’s skin—making this a most immersive and irritable spectorial ride. Through his glamorous vignette and methodological approach Fasulo offers commentary on societal elitism and narcissism, and how a simple misstep can find you marginalised and cast away to a point of no return. Why is it we seek such vile membership so ferociously? This is one of Dorsia’s many secrets. Chapó Federico Fasulo. DOSE ★★By Adrian Perez

Dose tells the story of a scientist pushed off a precipice of delusion and hysteria via the military, in their pressure for him to come to a vaccine and long-term remedy for schizophrenics with grave Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. Dr. Berg’s (Palabiyik) methodologies are so drastic and barbaric in combating the interiorised illness, he’ll see his own wife become a victim of a VR experience gone wrong. Dose’s production scale and design are its strongest suits, as well as the cast particularly Roberto Puzzo’s performance as Lt. Fox; perhaps were Dose retreads from conquering higher ground is in its screenplay’s lack of depth and rationale for the many events unfolding in front of us; why are these methodologies employed? Has humanity become largely-schizophrenic to the point we are all locked up in psychiatric cells switched onto VR (very much like in the Wachowski’s Matrix)? Many questions are left unanswered to the point that the short on first watch pushes past unambiguity to misreading. Questions a voiceover narration could tackle to help establish the world we’re inhabiting in Dose. A formidable debut on Kuerten’s part for its technical merits. EEMBER ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Ember strikes a nostalgic chord immediately in its opening scene of a post-robbery meet up. Though Lahr cleverly implants the idea that these three robbers won’t fair well—from his intertextual link to Reservoir Dogs— he shifts past Tarantino’s one-location narrative stylisms to his own terrain; preoccupying himself with exploring Chris’s (Weber) inner psyche and humanity ahead of his crime(s). Ember can feel jampacked to the point we are met with important fatalities we don’t have time to digest nor show care for; that’s the challenge of working within such runtime and small canvas. One thing’s for sure, Ember with its likeable cast and non-linear shifting keeps us on our toes and entreats us to a wild and raw ride. FFAITHFUL ★★★By Adrian Perez

I’m a fan of Faithful for its retro-thriller editorial style that throws me back to classics such as Basic Instinct, Unfaithful and 9½ Weeks. Berggren’s psychological drama is half-brewed; where its cinematographic and editorial pillars raise up its calibre, inconsistencies in its performative and auditory facets condemn the opposite effect. Dialogue at times though minimalistic, which I favour, proves contrived. Technicalities aside, Berggren’s Faithful is a homage to the genre, boasting passion for classical storytelling whilst allowing for contemporary screenwriting in its finale twist. Faithful depicts deceit and denial hand-in-hand and the toll it can take on our psyche to a point of no return. I long to witness Berggren’s evolution in his career, I like where this director is going with his craft. FALL BACK DOWN ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Fall Back Down is essentially a story about boy meets girl(s), whilst obedient of a rollercoaster story structure, nothing’s conventional about Sara Beth Edwards’s romcom for it breaks social barriers and deeply-rooted socio-cultural ideals, and fights for the greater good. Whilst many films poke fun at millennials for their narcissistic brattish demeanour and interdependence on technology/social media, here’s a film that stands for millennials for their liberalism, sexual fluidity and activism. Whilst not overly obvious to start with, it’s a powerful underlying message that surfaces quite vividly in the finale, I’ll try not to divulge spoilers as to how. Edwards pens a quick-witted script with majestic exposition and has most charismatic leads at the helm of this bohemian ride, the film boasts in superb comedic timing. Fall Back Down’s cross departmental efforts all-round are commendable, Nick’s story is wrapped in most intricate scenography and a fabulously eccentric edit. There’s little to contest, Edwards’s quirky story and characters are infectiously loveable and vulnerable, the film relies on the all-time favourited genres of romance and comedy to be the canvas for this forward-thinking story concerned with social consciousness and above anything—personal freedom, for we all have the right to it. I can imagine a more mature demographic will be shocked by some of the film's thematics, but I think it’s about time a film takes that risk and catches the spectator infraganti. Hollywood are still taking baby steps in depicting the transversality of sexuality by introducing cameo gay characters. Edwards unapologetically takes the world by storm. GGAIA ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Juan Zuloaga Eslait creates in Gaia a biblical I Am Legend, where perhaps humanity has a chance whilst it’s at the brink of extinction. Francis, played by the captivating Matthew Clark, finds such chance to be slim when doomed to loneliness by the mute detached Evelyn (Madison DeVries); who in holding onto the vase of her dead daughter repeatedly endangers her life and that of Francis’s. It’s in salvaging the vase in an impossible moment that he earns Evelyn’s trust, to which she contends whether it’s worth them saving humanity (through procreation) for it lays in their hands. Despite mankind’s self-inflicted bloodshed and death, and contribution towards earth’s destruction (for which Eslait makes a remark to contamination in Francis’s water bottle mountain collection), they give into each other, for they can’t battle nature in their own hearts. Eslait exhibits flashes of sheer artistry in his juxtapositions from the two-hander narrative to nature giving life; in a birds nest cracking, and even a small leaf battling its way out of a concrete crack. If anything, Gaia would have conquered higher ground had Eslait exploited these choices more to push the film’s avant-garde value, a signature stylism of Terrence Malick’s, employed formidably in The Tree of Life. Though ravishing to watch with Eslait showcasing this ethereal scenography through lens flares and a hair-raising orchestral score, Gaia feels half-brewed; indicative dialogue wake us out of suspension of disbelief, and the stakes of the story never feel grave enough. Since humanity’s only chance lays on this modern Adam and Eve duo, one of their lives should come under threat in a more dramatic “biblical” way. There’s plenty to love whilst also contest in Eslait’s new epic. Ambiguity overrides exposition in Gaia making for a poetic visual spectacle. GHOST IN THE GUN ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

It’s fun to see the western genre revitalised in this way, a magic pistol that entraps any vengeful soul upon death for their deed to live on and get passed on to whoever uses it next. Chen takes his high-concept and runs with it to a cataclysmic final moment that finds the “Ghost in the Gun” and Agoston Krug (Bridgett) conflict in their pistol’s aim when confronted with the two men responsible for their personal worlds collapsing. Chen takes us on a supernatural western odyssey that’s over too soon, all the more merit for his short film’s pitch power for a feature-length treatment. Ghost in the Gun is superb in every way, from its intricate scenography, CGI and cinematographic calibre to its charismatic cast and editorial styling. Much like the film’s magic gun entraps vengeful souls, Chen’s debut hooks our eager souls into wanting more. Superb in every way. GHOSTLOVE ★★By Adrian Perez

Ghostlove’s strongest asset is its story’s underlying high-concept for a bigger feature-length cinematic spectacle. It’s most fascinating to learn of Chinese ghost marriages here, a 3,000-year old tradition that lives on and not the only culture that upholds it; other forms of ghost marriage are practiced worldwide, notably in France and South Sudan—in these terrains called posthumous marriages and levirate marriages. Palm is everything but devoid of creative ideas and the film’s possible downfall is due to their disjointed arrangements; whereas Hsu’s animalistic dance choreography to depict Sophia’s ghost longing for eternal life through Alex’s (Hernandez) hand in marriage is a treat for the eyes, it sways the spectator too soon from the big bomb Yuka (Landon) drops on Alex in asking her to marry her deceased daughter. Palm opens a can of questions and whilst many remain unanswered, we’re also shocked at Alex and Yuka’s pacific demeanour and lack of exteriorised sentiment as they converse over someone very close and dear to them. Ghostlove remains one-levelled throughout and demands more dramatic and comedic oomph. Palm is sitting on a formidable concept and now just needs to think about how to better orchestrate the arsenal of storytelling and cinematographic tools at her disposal to tell her compelling story. HHINDSIGHT ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Hindsight makes unlikely friends in Mr. Raymond and Nathan, both societal castaways in their own rights, Ray for being a black blind old man and Nathan a disowned/repressed white homosexual young man. As disparate as these two characters can prove in their exterior, they’re very much stuck in the same pit of solitude, rotting away in their gruesome living conditions. Though Ray is blind, he sees Nathan more vividly than anyone and manages to awake him from his cyclical mundanity to strive for greatness and get out of their pit; for Ray is doomed, but Nathan has his whole life ahead of him. Kent delivers through his unique lens yet another compelling drama with a life-defining turning point for its coming-of-age protagonist. Whilst Heartstruck served a canvas to examine the volatility of chance-encounters at the hands of spontaneity, Hindsight reasserts such experience’s redemptive effect at the hands of destiny. Kent’s at the top of his game. IIN SPAIN ★★★★By Hannah Brown

In Spain paints one woman’s journey through the city, suspended between two moments in time. Ahn Sangwook’s filmmaking invites us to this pocket of contemplation for four gentle minutes. Clearly familiar with his subject matter, Sangwook captures the alienating magic of being a stranger in a strange place with a sensitivity rarely achieved in short film. In a palette that alternates quietly between sun-soaked, sparkling vibrancy and muted pastel tones, our protagonist, Eunsoo, walks through the almost unbearable nostalgia of memories couched in the place that bore them. Using lenses that sometimes illuminate and other times obscure, Sangwook embeds the feeling of re-tracing old footsteps. Except, upon returning to old ground Eunsoo must observe the memories she deposited there through various distorting and impenetrable panes of glass. Submerged behind a newer reality, we feel as though we are being shown an emotionally-redolent museum exhibition of her former life. The director’s confidence with colour and photography is obvious and it allows him to communicate that something profoundly important has been lost here. Yet, ‘In Spain’ lingers on a sublime sense of rejuvenation in the washing away of a past version of yourself and your relationship, as Eunsoo climbs to a superior vantage point over this city of her remembered love and pain in the slowly fading dusk. There is a wonderful appreciation of movement in Sangwook’s micro-short and he makes the most of the tension between private moments and public spaces. As Eunsoo slips into and out of the tidal currents of city crowds and Sangwook cuts between past and present, her face reveals that some flashes of nostalgia are more destabilising than others. There is a glimmer in her eye as she pushes through the now-lost joy and braces herself against the lavender evening light. All of this is set seamlessly against classical music that carries us safely into this finite meditation on place, memory and healing. A tender and recuperative piece of craftmanship – I look forward to seeing the emotional and geographic terrain this director chooses to explore for us next. |

ÎNTRE CHIN SI AMIN “BETWEEN PAIN AND AMEN” ★★★★★By Adrian Perez

Toma Enache’s Între Chin Si Amin will have you gritting through your teeth, for we wish this was a work of fiction but is a historical account of a time not too far behind us. Enache has us kidnapped and shoved into Pitesti in Romania from the get-go—hell on earth; for this is where hundreds of the youngest and brightest multi-disciplinary students were tortured in a radical brainwashing experiment from 1949-1952. Their only crime being their elitist background and religious faith in God—a threat to the Bolshevik communist ideology and dictatorship. We are entrapped in this brutalist experience through Tase’s lens who is arrested/kidnapped for being the son of a priest and having composed an Ode for God in Vienna. Him and his brother are shaved, stripped naked, physically tortured, and some crucified—broken in all the ways imaginable to surrender their faith. Enache showcases directorial artistry in his orchestration of picture and sound to create a tense and hyper-visceral spectorial experience. Our only escape from the prison madness, Tase’s happy memories with Lia. Între Chin Si Amin exhibits the highest cinematographic and scenographic calibre, boasts a hair-raising score, spectacular cast and standout performance from Vali V. Popescu. Brutalising, paralysing, a film that creates great impotence for its viewers, but paramount to watch. One of the best and most harrowing films of the year. KKILLING TIME ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Killing Time grants us a rare masterclass in one-location and low-budget filmmaking. Lovorn proves an autodidact powerhouse of a filmmaker; his onscreen performance is both compelling and intricate, offscreen he exhibits a most agile command in the film’s editorial, auditory and cinematographic architecture. Lovorn encapsulates in all of the film’s technical facets, a true testament as to the level of ambition and inventiveness we can accomplish if we let our imaginations run free and implement our limited resources to our advantage and not to our demise. A film that could have well been birthed during 2020’s pandemic lockdown and in its own right is one of the best self-made films of all time. KISS THE GROUND ★★★★★By Adrian Perez

Whilst we can get so bogged down in our own personal lives and problems, the Tickell duo remind us of an agenda we’ve long prolonged, that of respecting and caring for mother nature. Kiss The Ground’s powerful message couldn’t have been made clearer in the documentary film’s final statement to “restore a little bit of paradise every day”. I commend the Tickell duo for their formidable argument architecture through the film’s cohesive and engaging editorial arrangement, for many of us are not educated as to our daily contributions to global warming, which we have to stop at once. From desertification to regeneration, the Tickells hold our hand through our current agricultural and existential ways and exemplify through derivative NASA/NOAA schemas, models and statistics, and expert testimonials, of our mass agricultural miseducation and lack of political intervention in causing chronic stress on the soil (“desertification”). Once we’ve been educated on core ecological principles, the documentary invites us to apply our recently-found guilt and fear arousal into practical ways that can amount to the earth’s salvation (and our salvation); through changing our nutritional sources and composting more as primary examples. Processes that amount to soil regeneration. It’s most fascinating to see Josh and Rebecca Tickell compare farming terrains to demonstrate regenerative agriculture and the resilient/risk-free long-term benefits that come from managing farms for soil health. Kiss The Ground boasts in its wealth of educational content and guidance, it’s then in its editorial construction and influential celebrity interventions that the Tickells aggrandise the topic’s appeal for it’s undoubtedly one of mankind’s most neglected preoccupations. Where I think the documentary could have conquered higher ground is in expanding the nutrition argument; the Tickell duo only scratch the surface as to the benefits of plant-rich food and grass-fed meats for nutrient density. Dr. Steven Gundry’s Plant Paradox diet expands on the Tickell’s core principle for what it can do for the soil to how it can also amount to our longevity, and cardiovascular and intestinal restoration from the hazardous effects of lectins. Just as we’re drying up the soil through our incessant tilling and spraying of toxic chemicals, an interesting comparison can be drawn to what we are doing to ourselves internally by consuming junk food with high levels of lectins, which are essentially addictive chemicals that trigger our intestinal microbes to thirst for more, and making ourselves susceptible to obesity. The Plant Paradox diet which both the Tickells and Dr. Gundry advocate, as well as a key ecological principle, is also key to minimising heart disease (for lectins block up our blood vessels) and eradicating obesity, which the rate in America in 2019 was 39.6 percent. The Plant Paradox diet argument which was just scratched here, I would’ve liked to have seen expanded for it incentivises change, not just for the soil’s longevity but for our human longevity. A remark to 2020’s global pandemic’s anthropause this year—which amounted to 25 perfect reduction in carbon emissions and 50 percent reduction nitrogen oxides emissions—would also leverage Kiss The Ground a bit more. Though already in motion in the festival circuit, it could be revisited ever so slightly to ensure its documentation is up to date and contextualised to the world’s current stance. These mere suggestions are in no way detrimental downfalls, but testament that the documentary’s effective and engaging in triggering commentary and debate. Little can be contested, the Tickell duo condense years of study, research and hard work into a ninety minute documentary that’s most insightful and relevant, wrapped in a slick, interactive and authoritative presentation. A high-calibre documentary. LL’OBSERVATRICE DÉTACHÉE “The Detached Observer” ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

L’observatrice Détachée is a captivating art film for the avid eye to dissect from the get-go. Every frame is intricately-composed to make up a surrealist oeuvre that sparks similitudes to German expressionism, Surrealist Cinema and Hitchcockian Cinema through the use of eyes in the film’s penultimate composition; a vignette that confronts us with giant surveying eyes through every single frame hang up on an abundant gallery wall. Marija depicts dreamlike horror through collage juxtapositions of time clocks submerged underwater, surveying eyes and traffic jams to resemble her interiority and state of existential crisis and suffocation. It’s then in accompanying these problematic canvases with the content of Moreu’s exquisite narration—that we come to deduce all these feelings of angst to be inflicted by our very societal infrastructure. A matrix that impels conformity and normalcy. Marija’s director statement further confirms her desire for this film to rebel past regulatory ideals to proselytise non-conformity as the key to personal freedom which is the highest form of success and happiness we can strive for in the Wachowski Matrix that we live in. Marija’s poetic film is exquisite to watch and decode. I long now to see Marija employ her artistic impulses and influences within a long-form narrative canvas to perhaps give rise to a new avant-garde movement. LADY USHER ★★★½By Adrian Perez

There’s nothing safe or predictable about George Adams’s Lady Usher, a film that majestically creates horror out of defying our socio-cultural ideals through a family legacy of incestry. Lady Usher is in fact based on Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Fall Of The House Of Usher. Though Adams’s exposition is unhurried, we persist through much of the film to uncover the mystery behind this desolate mansion and Lady Usher’s rules, and why she has her son Roderick tormented and wrapped around her little finger. Morgan proves an unorthodox heroine, for instead of running the other way at the sight of some grotesque phenomena, she stays to fight for a place in this perverse family as Roderick’s girlfriend. A twisted tale that whilst pokes at forbidden promiscuity between family members in consanguinity, is fundamentally about feminine rivalry in conquering a weak-spirited man; the son in this case is nothing more than a passive object of desire to squabbled over by competing matriarchs. I commend Adams’ fresh concept and sublime Shakespearean dialogue; where the film could have conquered higher ground is in more tension-building and a rising hysteria depicted through more cinematographic interiority and an even more surrealist rollercoaster screenplay. Had Adams turned-in a more hectic spectorial ride in the style of Aronofsky’s Black Swan or Guadagnino’s 2018 Suspiria remake, this would have been a home-run. Adams opts more for a poetic and underplayed Macbeth oeuvre; but where the film proves most entertaining is in its more bizarre vignettes, such as the hallucination of sexual trespass—where Lady Usher goes down on Morgan. A moment that could’ve led to a cascade of hysteria and surrealism, but the phenomena we do get feels a bit too spaced out. Adam’s Lady Usher though it begs for more avant-garde experimentalism, boasts an intricate scenography and charming cast, and holds enough of a reinvigorating concept and louring tone to keep us in suspense to the bitter end. LOST AND SPACED ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Roozbeh Tavakoli. Remember this name for we could easily be looking at a new household name in him in the next decade or so. What can’t be contested about Lost And Spaced is its fresh contribution to cinema and the craft of visual storytelling. Very rarely do I see an independent director employ a limited set of tools and resources at his disposal so inventively and to such impactful and great comedic effects. Lost And Spaced may not exhibit the best lighting or cinematography you’ve ever seen, but it sure puts on a show to remember. It’s quirky, fresh, exhilarating, hilarious, sensitive and ultimately confusing—and all the better for it. Once the curtains drop on this film it leaves us longing for more, hanging from a cliff, unable to digest the film’s final moments for how tragic whilst hilarious what we witness is. It takes a master of storytelling to make death comical, for that very fact Tavakoli can rest assured he was born to do this. The world is starved for fun, and Tavakoli serves it to us. Much can be appreciated and picked out from Lost And Spaced’s entertaining spectacle; from its surrealistic vignettes where Nathan finds himself deciphering his life with the help of a drag queen, a junkie priest and his father’s ghost; to the creative and hilarious sound design where the sound of a squeeze toy enthrals us as Nathan continuously gets punched or grabbed by the balls down there; to the exuberantly charismatic Joel Phillimore who plays the chaotic but lovable Nathan most authentically and effortlessly, a lead protagonist we truly vouch for. Lost And Spaced is a gem, it’s independent cinema’s best kept secret, I long to see Tavakoli’s passion and originality take him all the way so that the fantastically minimalistic and unpolished spectacle that is Lost And Spaced becomes an all-time cult classic. I celebrate Tavakoli’s work and vision. The world is dying to meet the talent powerhouses that are Roozbeh Tavakoli and Joel Phillimore. LOVE IS NOT LOVE ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

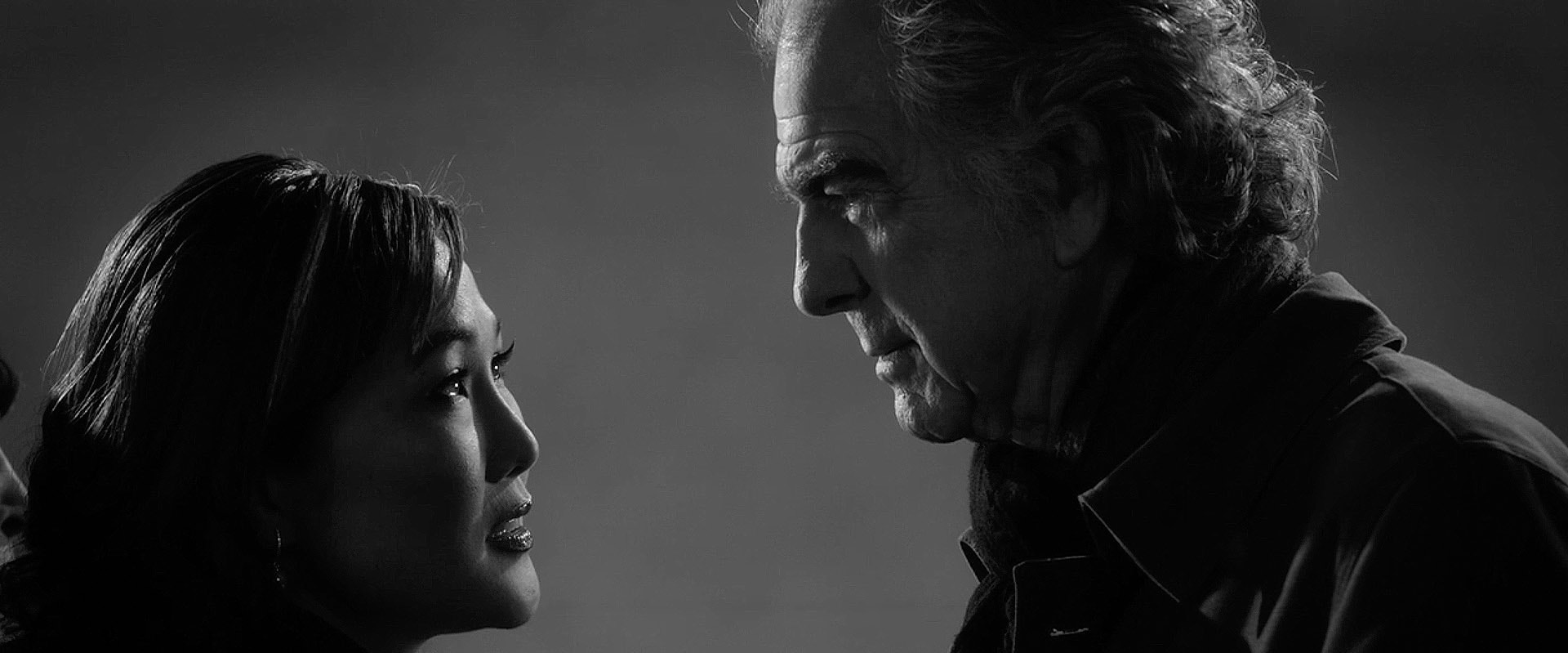

Love Is Not Love entreats us on a New Yorkian odyssey to uncover one of life’s biggest questions: what is love, really? Mills opts for film noir and his slick black-and-white presentation to set us on our detectorial case to decipher the mysteries of love, an ascertained visual choice that pokes fun at how it takes a lifetime of detective to work to figure it out, to experience it, to feel it, to digest it… Fadellin’s cinematographic work, whilst it amounts to a performative documentary, exhibits high-calibre; together Fadellin and Mills serve a homage to classical Hollywood in its Casablanca-esque vignettes, for example the moment when Frank (Mills) makes a short-lived connection with a woman of oriental descent in a line-up to consume art. A sublimely architected moment that strikes a nostalgic chord. Mills exhibits irrevocable talent in screenwriting, and particularly witty conversational comedy and physical comedy (through the street jesters); moments of sheer comedic brilliance that unquestionably rival and champion Woody Allen’s quick-witted philosophical humour. Mills’s latest canvas boasts experimentalism, interiority and artistry; whilst it also serves an arena to showcase his multidisciplinary talent as a writer, director and actor. Love Is Not Love swaps ultra-structure for ambiguity, and sets us off on this nostalgic black-and-white whilst extremely colourful odyssey to come to our own definition of love, with a little help from all its quirky protagonists and their off-the-wall testimonials and social scenarios. LUMINOUS ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Luminous is the quirkiest sci-fi film I’ve probably ever seen; we’re placed in this labyrinth of a guarding base with infinite ultra-futuristic corridors from the get-go, with an anime hologram as its AI system and a grumpy Mexican American guard behind its front desk. Niles deviates from mainstream stereotypes at all costs in his casting choices and choice of an anime hologram. All choices with an underlying sociocultural defiance for the media’s imposed preferences; choices which as a film critic I commend and in-turn make Luminous a unique attraction. Luminous is intended to be a bigger vehicle; in the short’s just over eleven-minute runtime we get to indulge in its ambiguity through its impressive intricately hand-made underground maze world we’re wrapped into with infectious electronica music and gorgeous red blue neon lighting; entreated to pelvis moves to be envied on Borrego’s part and the adorable anime companion. As Luminous comes to its open-ending, a finish we never want to come to, we’re left with an infinitude of questions to answer; answers we’ll only be able to seek in Niles’s feature-length treatment of it. A film I’ll eagerly await to dive into. Niles is an infectiously stylish newcomer who the world is dying to meet. MMAGGI VARVARA: ‘BEAUTY BREAKS FEAR’ FASHION FILM ★★½By Adrian Perez

Fashion films are on the rise to omnipresence; snack-able audiovisual spectacles that could debunk music videos and film trailers as YouTube’s most popular types of videos in a couple more years. Fashion has inspired a new wave of ambiguous poetic cinema to the point that multiple film festivals exist to exclusively celebrate the thriving genre. Maggie Gu breathes life into her fashion line Maggi Varvara through her film ‘Beauty Breaks Fear’; an ethereal spectacle that blurs the boundaries between dream and reality, incarceration and infinity. Gu transports us to a land of dreams and opportunity when her two millennial protagonists cross over to this dream realm via a magical rose in a glass dome (much like the rose the enchantress leaves behind for the prince in Beauty & The Beast). Gu succeeds in her slick and soothing editorial construction, though the same can’t be said for the film’s cinematographic calibre. Though the rose offers a portal and marks a before and after, the world we’re transported to beyond, though heavenly, doesn’t feel fantastical enough and by the time we return we continue to feel a sense of neutrality as if we’d never left. I can’t help but feel the concept was only partly realised. What can’t be contested is that Gu’s film breathes elegance, class and style into her latest 2020 fashion line. MANARA ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Alexander looks at suicide through a rare lens, that of a family’s endeavouring efforts to destain their family’s patriarch once faced with suicide’s aftermath and the facts of the truth. Sociocultural ideals, family secrets/repressions, as well as differing coping mechanisms—in the form of Kübler-Ross’s cyclical fallacies of grief theorem—interplay in Alexander’s intimate character exploration. Results are triumphant, Alexander proves an avid autodidact director able to turn-in a career-defining performance on his part, whilst leading his cast to deliver subtextual micro-moments impossible to depict on the pages of a screenplay. Alexander’s directorial tenacity in letting the camera linger on and the void of silence prevail in its awkward pauses is to be commended. Manara is a rare, authentic, understated drama. One of the best of 2020’s, a year that sees many of us walking the tightrope of mental illness and mental health due to the pandemic. MARELD ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Blair Witch Project meets Battle Royale in this seafire (“mareld”) on a Stockholm archipelago. Ove Valeskog employs Mareld to be an experimental canvas in which he hopes metacinematography and hyperrealism intertwine to reinvigorate the spectorial experience. Valeskog sparks a new wave of metacinema that surrenders the spectator into complete suspension of disbelief, and whatever you throw at your spectator from there on out will be shock-inducing and destabilising to a point of distress. A film within a film, it’s not until the bitter end that we question the authenticity of the “documentary’s” events; Valeskog majestically wraps us around his little finger into believing what we are seeing. Both narratives within the documentary and fiction film depicted, get to the same morale, curiosity can get you killed. For the same mistake these tourists make in invoking the mythical “Mara” to the point one of them becomes possessed and goes on a killing spree, this film crew trespass a “military” camp (undercover illegal operation) to the point of a massacre. Whilst Valeskog’s concept and methodology is fresh, Mareld feels a little bland and slow-moving at times. Valeskog deliberately makes the fictional movie being filmed rather pedestrian, so that the events of the documentary call for our attention and immersion; had Valeskog devoted more running time to the mystery of the military camp the film would’ve been more entertaining. Calibrations aside, Mareld is bold and avant-garde and boasts cinematographic calibre and stellar performances from its top-notch cast. MISS YOU, DAD ★★★½By Adrian Perez

Miss You, Dad’s biggest success lays in the fact that the perpetrator isn’t outwardly obvious. Time and time again we see even the greatest storytellers deceive their villains by making them outwardly grotesque and menacing from the get-go, whilst the leading villains in cinema hide behind a timid unsuspecting facade; such is the case in Zaveri’s film who presents us to an adorable paternal figure for Ava in Clohessy, who to our surprise then violates the spectator in his immoral trespassings. It’s in this single performative decision that it owes much of the film’s success, I have to applaud the casting choice in Clohessy, who turns in a bewitching and most memorable performance. For both a student and directorial debut, I have to commend Zaveri for exhibiting great creative tenacity in her story’s non-linear world-building. Miss You, Dad will deceive you and break your heart, much like Ava’s torment. NMY DEMONS ★★★By Adrian Perez

Elena’s (Nohrstedt) existential crisis and impotence in piecing her life back together leads her down a precipice of prostitution, drug addiction and toxic relationships to a point of no return. Carselind’s command of the film’s editorial construction and auditory engineering are its biggest attractions in directly immersing the spectator in Elena’s interiorised hysteria; My Demons boasts in its story substance and immersive architecture; its only downfall lays in a need for more ambitious cinematographic and performative treatments to rival its counterparts. Carselind turns in a most mature film, utilising her canvas to delineate anxiety disorder, psychiatric depression, substance abuse and addiction, and ultimately self-destruction; it’s in minor all-round technical details and refinements to her craft that Carselind needs to exhibit growth to truly boost her audiovisual work to transcendence. Carselind proves an ambitious filmmaker to watch. NOC - NON-OFFICIAL COVER ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

NOC - Non-Official Cover is a pilot that ticks all the boxes, its perfectly-calibrated recipe invokes infectious laughter whilst plenty of room for character depth. NOC owes much of its success to its quick-witted script and phenomenal lead in Brady, whose comedic timing and emotional profundity come hand-in-hand in creating in Richie Jones a lead protagonist we truly vouch for. NOC is a fabulously eccentric pitch vehicle to green light a series, which would see Johnny English’s more handsome and mature American sibling take over our screens. More and more content is depicting the hardships of the working actor’s life, but none poke fun at the profession like Voglesong and Swift do; though some of its vignettes are surrealist and cringeworthy—they’re as real as they get. It’s in penning this to be a dramady that this powerhouse of filmmakers unleash a fresh lens through which to depict the mysterious ways of the profession. One of the best pilots of the year. OONLY DEATH NEVER LIES ★★★★★By Adrian Perez

Only Death Never Lies is a rare exploration into male emotional repression and toxic masculinity. Yazdanpanna and Henrichs’s intricate world building for metaphorical and subtextual effect is formidable yet again in their latest collaboration after Unity; there’s something poetic about a boxer being able to stare death in the face each time he steps on a ring arena, but then is unable to look at his dying grandpa in the eyes. Yazdanpanna once again proves tenacious and inventive in his directorial choices in telling this gritty urban drama, from his cinematographic language to his cast’s understated and potent performances. Both Fardi and Javdan turn-in career-defining suspension of disbelief in their nephew/grandpa duo performance; whilst Henrich is on top-form yet again penning transcendent philosophy in his new one liners. Only Death Never Lies’s vigour is due exclusively to its powerhouse filmmakers who I wish to see collaborate again for they’re leading Iranian cinema. OPEKA ★★★★★By Adrian Perez

Opeka is a documentary we wish to be fiction, for it depicts the landfill hellscape that is the poorest country in the world—Madagascar. Cam Cowan much like Father Pedro Opeka is a one-man band, together they join forces to remind us through the power of the lens that sometimes all one needs to build an empire is a little faith and hope. In a neglected land that finds its people marginalised and defeated, passive and hopeless; Father Pedro comes along to inject hope, resilience and proaction back in their lives for their children’s future. As the documentary ensues we see Akamasoa’s children forty years later become teachers, doctors, social workers amongst many other respectable professions that give back to the community. Father Pedro’s life mission in uplifting a community to collaborate with one another to literally rebuild their lives is admirable, and whilst this life devotion and vow comes from a place of heart, I’m thrilled his work is repeatedly being recognised for the Nobel Peace Prize. It’s in all the images of Father Pedro parading through streets and landfills clang on by children that the documentary creates a hyper-visceral impactful spectorial experience, where we see reality and biblical prophecy collide for Father Pedro for these people is a Godsend, much like Jesus, a reincarnated Messiah. This restorative energy transcends beyond the onscreen onto our own belief system and cognitive infrastructure, for it restores our faith in humanity for one man today is saving people’s lives and setting an example. The power of one. It’s in Father Pedro’s final moments and preparation for succession, that he pledges succession will rise naturally. This documentary deposits its divine power and weight of social consciousness upon anyone who comes across it, inspiring action; which starts with small acts of solidarity and kindness, much like Father Pedro’s first baby steps in helping Malagasy people upon his arrival in 1970. Cowan’s Opeka doesn’t explicitly function to be a plea for help, his unobtrusive documentarian methodologies (both editorial and cinematographic) simply provide a looking glass onto our world today, it’s solely in its brutalist imagery that it evokes action. In a western world where elitism and narcissism coexist with chronic malnutrition and extreme poverty, Opeka makes a stand. Destabilising and transfixing, Opeka puts Madagascar back on the map and humanity back on the agenda. PPROOF OF LOSS ★★★★By Adrian Perez

Nothing inflicts a reboot and a chapter-marker than your home’s demolishment via a natural disaster; in Proof of Loss’s case we see the real-life father/daughter duo in the McDermotts lose their fictional family home via the consuming flames of a mass forestal fire. Proof of Loss serves us astonishing suspension of disbelief in the apocalyptic hellscape the real recent fires of Northern California left behind; having both Dylan and Coco McDermott transverse their real life bond as father/daughter into their fictional roles of the same dynamic also amounts to this rare cinematographic achievement. Fisher’s latest exercise is an intimate character study and metaphorical depiction of the aftermath of loss; and how our individualised coping mechanisms for loss are very much incompatible to that of anyone else’s. Fisher acutely-calibrates both father/daughter’s coping strategies from denial, anger and sorrow and has them both cross an abstract tightrope to one another in the hopes to emotionally reconnect after wife/mother left a void in their lives; it’s in the duo’s tempo-rhythmic performative constructions, which are both understated and compelling, that this film boasts with authenticity. Fisher serves a film that’s proof of cinema’s power in mirroring our souls and the depth of grievance we carry within. RRED: A FAIRY TALE ★★★By Adrian Perez

Having a vast audiovisual portfolio under his belt, Turner’s at a point in his career where he’s taking the canvas of film and employing it in fresh new inventive ways. Here in RED: A Fairy Tale he subverts the timeless cautionary tale of Little Red Riding Hood to forewarn that we can be just as much of a danger to ourselves than any other external forces. A self-contained and ambiguous poetic film which creates an insatiable curiosity once it’s over; perhaps its only detriment is that the underlying message doesn’t cut through on first watch. It really is in the film’s technical calibre that RED shines; Turner and Alva’s tenacity in the film’s editorial construction and visual effects to convey interiority and create an immersive spectorial experience from the get-go is commendable. RED showcases how far an autodidact filmmaker can go in creating a film to be envied for its competent technical calibre. Here in RED we have a cinematographic exercise that boasts in experimentalism and modus operandi—making Turner an exciting newcomer director to keep an eye on. REFLECTION ★★★½By Hannah Brown

Martin Ristvedt’s autobiographical animation writes its own visual poetry to depict the deeply personal experience of growing up as a non-binary person with asperges syndrome. Throughout this bildungsroman micro-short, the imagery finds its roots in elemental nature from and of which the aptly named protagonist, Bud, springs. Fantastical, pigmented frames plunge Bud into the foetal position amongst the crimson flower cups, faltering quickly into ice-cold serenity amongst frozen fractals. For fear of simply singing the praises of Ristvedt’s animation prowess, I can’t help but acknowledge the astonishing artistry that characterises this bachelor film. There is wondrous attention to detail in frames such as that of the grand piano in a desolately empty room, bustling with flora that grows from within. Through each window a different phase of day shines and this Dali-esque motif for the plane of understanding between the internal and external world comes into its own as Bud approaches their final stage of re-birth. It’s a shame that the audio recording used for Reflection’s voiceover was of a lower quality and left me wondering whether one of the film’s weaker points might be the script itself. I would advise Ristvedt to be careful not to wander into the abstractly vague when writing such private thoughts and processing of the world. That more encoded emotional rendering should retain its impact visually instead, where we are subjected to amorphous and enigmatic motifs and symbols. As Bud’s figure transforms fluidly from flower to skeleton and eventually a marionette with a shattering and splintering head of glass, Ristvedt’s imagery becomes more disturbing. Though this echoes Bud falling into destructive and despairing moments in their life, there seems to be an unwelcome shift into what is essentially horror here, with melting strings of limb flesh separating to release a bloody-like aura that dissipates amongst the disembodied corpse. Ultimately, to see such delicate artistry and a rich symbolic style in a student film leaves me in eager anticipation of what is to come from Ristvedt. Reflection demonstrates a mesmerising capacity to make interpretable to others the innermost workings of a mind confronted with a bewildering and isolating reality. An astonishing début. RIDE WITH THE GUILT ★★★★★By Hannah Brown

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through The Looking Glass, a young girl climbs through a mirror into the curiously inverted world beyond. In succumbing to her land of fantasy, Alice exhibits behaviour we would now read as the actions of a sufferer of paranoid schizophrenia. As the rain lashes down outside, Ride With The Guilt stuffs us into a parked car beneath lashing rain where an Alice in Wonderland bobble head stares lifelessly from the dashboard. Dario Bocchini proceeds to transform this claustrophobic setting into Monica Caravan’s own neurological hellscape and her guilty conscious sits firmly in the driving seat. His elliptical narrative throws us disturbing fragments of memories and revelations, mere shadows of Monica’s implied actions: a bloodied cot and bloodied hands. Her rapid emotional unspooling leaves us desperate to understand who she is and what exactly she has done. To answer these questions we too must surrender our grip on reality and step through the (rear-view) mirror into the ruptured psyche festering beyond. Ride With The Guilt is an agonising meditation on a relationship experienced through the dark lens of Psychosis and Borderline Personality Disorder. Bocchini casts into ambiguity the true state of Bruce and Monica Caravan’s marriage. Instead, like Monica, we are left alone with her conflicting interpretations of how things stand: is Bruce the perfect husband, or the devil that gives her a little push towards murder? Not one to miss the opportunity for symbolism, Bocchini reveals in flashback through canted angles that Monica’s head tilts just short of perfect alignment with the devil horns on the mantelpiece behind her. Frame-to-frame this film feels like walking the emotional tightrope of Monica’s unravelling psyche. The rope comprises two entwined threads of identity: her anxious, vulnerable self, and her guilty conscience. As Guilt, Clarice evolves from advisor, to interrogator, victim and finally accomplice. Awash in hallucinogenic lighting, Clarice and Monica wrangle with their innermost desires and fears until these fractured voices of Monica’s subconscious converge within one very real and very dangerous body. There’s much to commend in Bocchini’s filmmaking, which takes an economical approach to location selection and a rich adornment of those sets with symbolic details for us to savour. With the violent Monica re-awakened by the film’s end, our final view is from the perspective of the boot and if I could ask for anything it would be for this shot to be held for the entire ending of the film, in slow motion. In a film that considers suffering within the framework of a marriage, we cannot ignore the possibility that Bruce had been a manipulative husband who undermined their relationship with abuse and coercive control. Perhaps Monica’s shame and paranoia are the cumulative result of his treatment of her. As such, there is something intrusive about Bocchini’s role as director of this portrayal of woman and victim. Where Monica’s husband is absent, the camera is always present; inside or peering into the car, invading her thoughts, pervasive and unrelenting in its documentation of her pain. It becomes all the more pertinent then that her final reclamation of control over herself shows her bring that hammer down cathartically into the cramped car boot inhabited now by both Bruce and Bocchini’s prying lens. Ride With The Guilt takes the trope of the bunny-boiler and casts it into a vitally ambiguous light. Bocchini refuses to answer our questions as to who has wronged whom here, but instead transports the horror femme and her Shakespearean thirst for revenge into the contemporary framework of mental illness, identity and motherhood with unambiguously triumphant results. SSECOND CHANCE ★★★★

By Adrian Perez

Through Tara Notrica and her family’s daily battle against her rare diagnosed Mast Cell Disease, “Second Chance” proves more than just an informative documentary but a philosophical odyssey; that reminds us not to underestimate the power of family and unity in overcoming hardships, however imperishable they may prove to be, as family can be the most potent cure. Matthew White and Brian Gerlach’s omnipresent lens don’t leave a moment unseen, a documentary that sparked a two-year audiovisual project and longitudinal case study. Through the good and the bad, White and Gerlach depict mostly the good, for “Second Chance” inspired an unrivalled depth to Tara and Samantha’s (Tara’s daughter) lyrical work, leading to Samantha finishing an anthemic album with 11 empowering songs. This resilient family teach us how we can’t control what happens to us, but we can control how we react to the external forces that face us. Through this uplifting documentary that sees Tara and Samantha proactive and finding more healing in the recording studio as opposed to clinical hospital settings, we see Tara move towards her fate in a risky bone marrow transplant operation and Samantha towards a record deal. By the end of the documentary, Tara is discharged 60 days post-transplant and is making a steady recovery. A miraculous outcome for this mother-daughter duo who defeat a mostly incurable illness through the healing powers of music, and can now look forward to a promising chapter for Samantha’s album has a raw power that not even Taylor Swift can rival. White and Gerlach’s performative documentary depicts a family striving for an ordinary life wherein nothing about their life is normal. That’s what’s most inspiring about “Second Chance”, how Tara makes a stand and decides the show must go on and that life dreams and projects must prevail in the road to recovery. Raw and powerful. SHORT CUT ★★By Adrian Perez

Everything in Short Cut can be bought, from a wife to a job or so it seems, until Vinay and Arun’s scheme to bribe their autocrat in the hopes to be set for life turns soar to the point they end up losing their personal fortune and are left with nothing. Singh and Kumar serve us a cautionary tale of corruption, one that though witty, feels disjointed and half-done at times. For a directorial debut, this creative duo manage to show off their comedic chops and talent—the scene where both defeated friends find themselves scratching their backs as the walk off is my favourite—whilst exhibiting a need for all-round growth across the film’s technical departments, something that comes with experience. Singh and Kumar should feel pride for their debut whilst beginning to think about what areas they need to refine in order to make their next cinematographic endeavour even greater. SHUTTER ★★½By Adrian Perez

Ramirez’s film feels half-brewed, though it boasts in splendid scenography and cinematographic calibre, it recedes in its indicative narrative and performative facets. Ramirez deceives his villain in making him outwardly obvious from the get-go, through his presumptuous demeanour. Had Ramirez concealed his murderer behind an unsuspecting innocent facade and created a shift in Harper’s performance, spectators would have been in for a surprise. Shutter exhibits a technical grip and command on the craft, now Ramirez needs to immerse himself in the mind of the spectator and think how he can tell his story in the most exhilarating unpredictable way. Scorcese’s Shutter Island or Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises are formidable examples of complots and anti-villains that are employed to take us by storm. A film to be proud of and one that’s exhibiting of great potential. |

SILVÀN - ALLEZ-LEUR DIRE ★★★★½By Adrian Perez

Silvàn’s music video for his new hit ‘Allez-Leur Dire’ depicts the weighty decision faring home and your roots can prove, quite literally. As Silvàn balances his desire to leave his pit of a home town with the few things holding him back, we find his suitcase gradually super-size itself to the point he has to push it as opposed to carry it. Humbert presents a ravishing visual metaphor of a music video to depict a common dilemma that holds many of us back; in playful fashion Silvàn’s catchy new song and music video ultimately implores the unknown must be explored, so go tell them (“allez-leur dire”). SKITOZ ★★★★By Adrian Perez

There’s no better bystander to attack with a deadly mosquito raid for effect than an old retired couple trying to relax out in their RV. The Perrotte twins subtly disperse cues as to Skitoz’s main story antagonist from the get-go, from Oliver (Boek) failing to resolve his crossword with the word “mosquito”, to the radio’s forewarning of an unprecedented plague of deadly mosquitos. The film slowly then leads us to the eruption that is this old retiree couple’s fatality via deadly mosquitoes. With a technical calibre that creates a magnificent suspension of disbelief, this exhilarating short film leaves us wanting to see the Perrotte twins behind the wheel of a bigger spectacle. In this short film exercise they exhibit extraordinary worldbuilding and tempo-rhythmic chops, I long to see them employ their tenacious directorial skills on a bigger canvas. SLOPPY JONESBy Hannah Brown

Sloppy Jones is *scandal* writ large. Picture an ensemble cast of queer twenty-somethings navigating their crappy jobs, sex lives and a whole lotta gossip, then go ahead and throw murder into the mix. Swill it and you are in for a slasher-comedy cocktail infinitely more delicious than the bar’s signature drink: the ‘Super Sloppy Bloody Mary’. With critically acclaimed drama director Winnifred Jong at the helm, Sloppy Jones rides the crest of its genre-rippling waves and refuses to slip into thin melodrama. Instead, we are treated to the unfolding intrigue of a live action millennial Cluedo, in equal parts ridiculous and frankly portraying the gritty glamour of life in your twenties. As a first episode, Sloppy Jones is virtually faultless. Jong succeeds in the difficult task of inviting us into the world of these characters and the hilariously morbid circumstances they find themselves facing, all in under four minutes. Thanks to Jamie Hart, Sophie Nation and Jonathan Neil Alexander’s script, the episode is structurally watertight. It creates exposition through individual character interviews and cleverly bookends them with ensemble scenes, anchoring flashbacks and comic off-shoots to the social and spatial parameters of this world. The inciting incident of Frank’s murder cuts us to our eyebrow-raising detective’s interviews with each suspect at the Sloppy Jones bar. These character monologues are executed brilliantly by a fantastic cast of actors and range in tone from the delightfully sardonic to the brazenly self-implicating. If I had to critique anything it would be the pacing of these back-to-back scenes, which though informative, could have been shortened to ensure the whole episode keeps us on our toes and bring home the montage-style here. It would also allow us to enjoy the scramble to keep up with the fly-by introductions to the characters and their more-or-less convincing alibis. Sloppy Jones inherits its quintessentially banal setting from the mockumentary tradition. There is little more depressing than a soulless bar in the daytime and, as in Its Always Sunny in Philadelphia, it provides the perfect backdrop of mundanity and lost dreams for its cast of cynical staff. Distinguishing itself from the crowd, however, the web series illuminates its lacklustre interior with dim fairy-lights and the noir streetlamps just outside. This lighting declares visually Jong’s blending of the crime-thriller and comedy genres. Sloppy Jones seats itself confidently amongst contemporary comedy shows, reading like Schitt’s Creek and embracing the breaking of the fourth wall we know and love from The Office and Modern Family. It does more than play these techniques for laughs, however. It is also showcases representation in comedy; a very welcome thing. Technical brilliance aside, let’s focus on the simple question of enjoyability. If given half the chance would I binge watch an entire series of Sloppy Jones? Yes, with relish. STARFISH ★★½By Adrian Perez

Buckner anchors her directorial debut on a plot-driven horror tale of adult nightmares, for human trafficking and modern-day slavery is omnipresent to this day. A 2019 United Nations report claimed there are nearly 40 million modern-day slaves in the world today. Gut-wrenching. Why is the film called Starfish? As grampa Pete claims to little Sam in the film’s opening vignette, helping return one starfish back to the sea doesn’t make much difference when the whole beach is covered in them; to which little Sam contests she “made a difference for that one”. That’s Buckner’s underlying message in her cautionary tale, saving one trafficked victim at a time though resource-intensive is significant. Not many films study the back-end of modern-day slavery and our lack of societal infrastructure in aiding a survivor who manages to make it out alive, Buckner forewarns action on everyone’s part. Buckner supports her vision with most intricate scenography and whilst we’re presented with a film that boasts in grandeur, it begs for a deeper exploration into Iris’s (Mahom) interiority; for in seeing what she has gone through we are only scratching the surface. What are the mental reverberations of such entrapment? Would you be the same person again? The story implores those interiorised interpretations and a more immersive spectorial construction to enrich our empathy for Iris. Starfish is a plea for help and a call to action. SWEET SUNSHINE ★★★★By Adrian Perez